Topographical mapping techniques rely on more than just contour lines to provide clarity and functionality. Their contour lines are almost always accompanied by other information conveying surface features such as ecological zones, roads of trails, settlements or other points of interest. Also critically important to functionality of these maps is their representation of bodies of water, be they creeks, rivers, lakes, or seas or oceans. This is because understanding an area’s topography and presence water is often related. Despite the breadth of information that topographic maps convey, one piece of information is almost always left out: underwater surface features, especially in rivers and lakes. Their graceful contours, which depict complex three-dimensional realities in simple two-tone images (black lines on white backgrounds) stop their communication once they arrive at a shoreline. I’ve always found this an arbitrary location to cease communication. The surface of the earth’s outermost crust isn’t the top of the body of water, it is the bed of the creek, river, lake, or ocean.

above: a screen grab of the Skoki Valley area in Banff National Park, Canada (Canada Topo Maps App). This high alpine area contains several large mountains and many glacial lakes. The hatched polygons represent forested areas (green), glacier (white), and moraine (brown). Despite the intensely varied topography, the lakes are represents as flat surfaces of water, without depth.

above: a screen grab of the Skoki Valley area in Banff National Park, Canada (Canada Topo Maps App). This high alpine area contains several large mountains and many glacial lakes. The hatched polygons represent forested areas (green), glacier (white), and moraine (brown). Despite the intensely varied topography, the lakes are represents as flat surfaces of water, without depth.

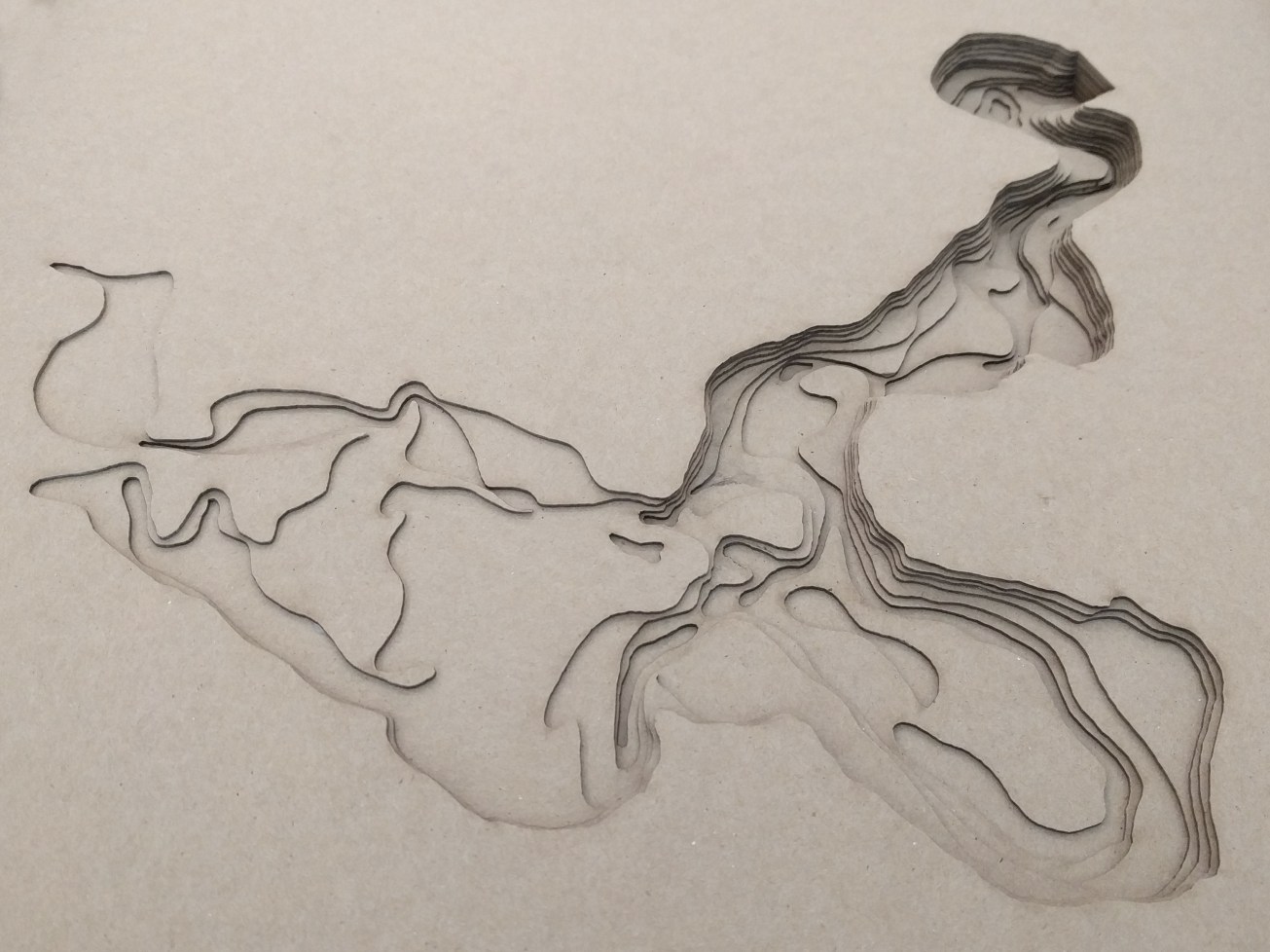

As a mean to highlight the forgotten information in these types of maps, I decided to play with the representational techniques of bathymetry (the measurement of depth of water in oceans, seas, or lakes), and bathymetry alone. The concept, or question, was simple: what happens when the typical techniques of mapping are reversed entirely, when information that is typically negated becomes the only information presented?

The Glenmore Reservoir, which is situated along the Elbow River in Calgary, Canada, was strategically chosen as a subject because of its own inherent issues of classification. As a reservoir, it is a purposefully consumed territory (a flooded valley), and also, as a result, it is a river/lake hybrid with dramatically young ecologies along its edges (a fresh line on a map). What’s also fascinating about reservoirs is the fading memory of their depths. Whereas a pre-dam map would have depicted the valley’s varied surfaces in great detail, a post-dam map treats the valley as essentially below zero (bathymetry generally counts down from surface, as opposed to counting up from sea-level), and despite once being a place where terrestrial life thrived, the valley now belongs to the unknown negative space of representation.

The dam in this context is a unique spatial circumstance, or an absurdity. Its sole purpose is to elevate the zero datum of the surface of the water, far above what is still the positive surface of the valley, on the other side. This creates a contradictory juxtaposition of representational information: on one side of a wall we’ll say -19m below surface, on the other +986m above sea-level, both numbers defined by a shoreline.

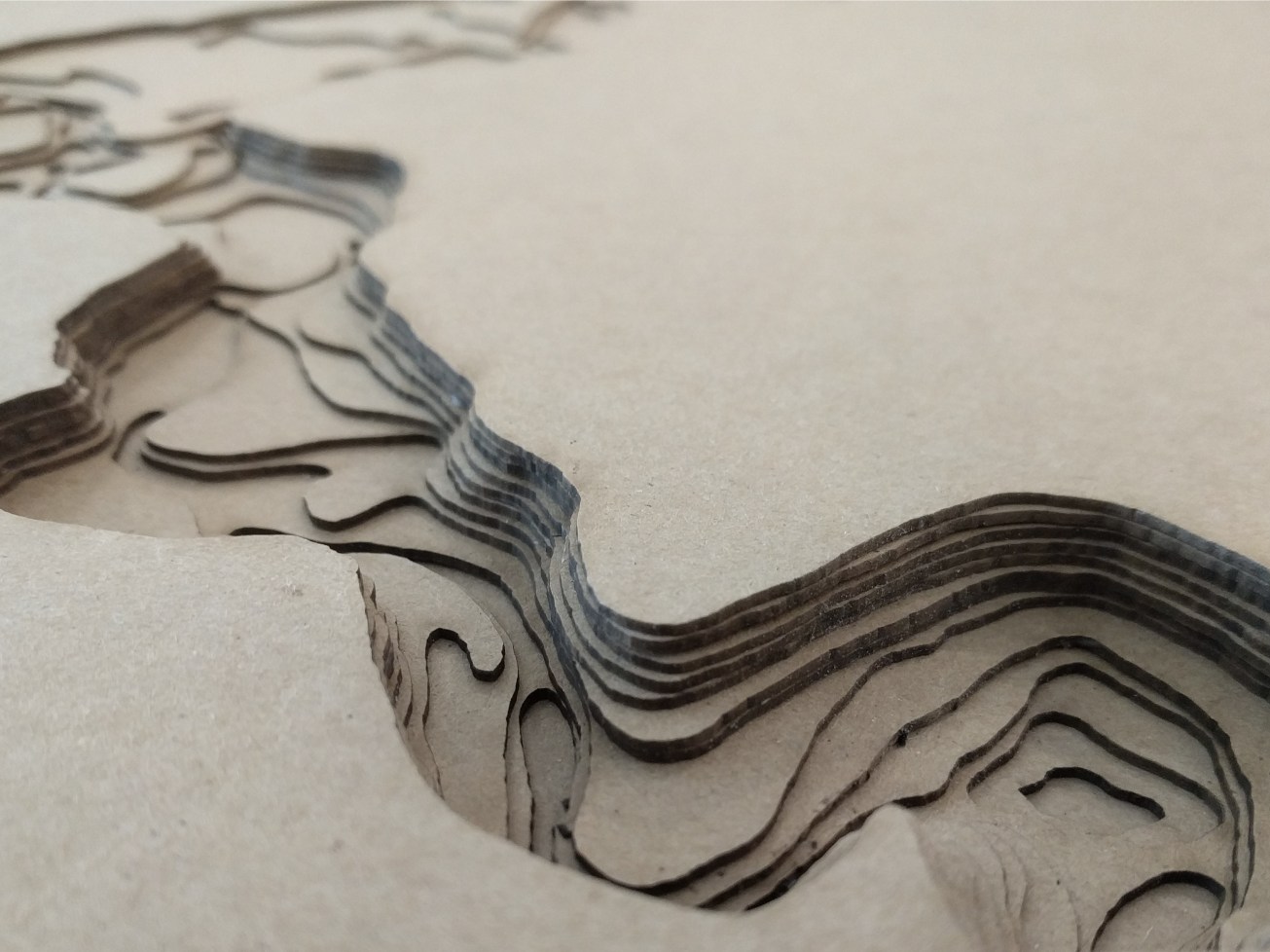

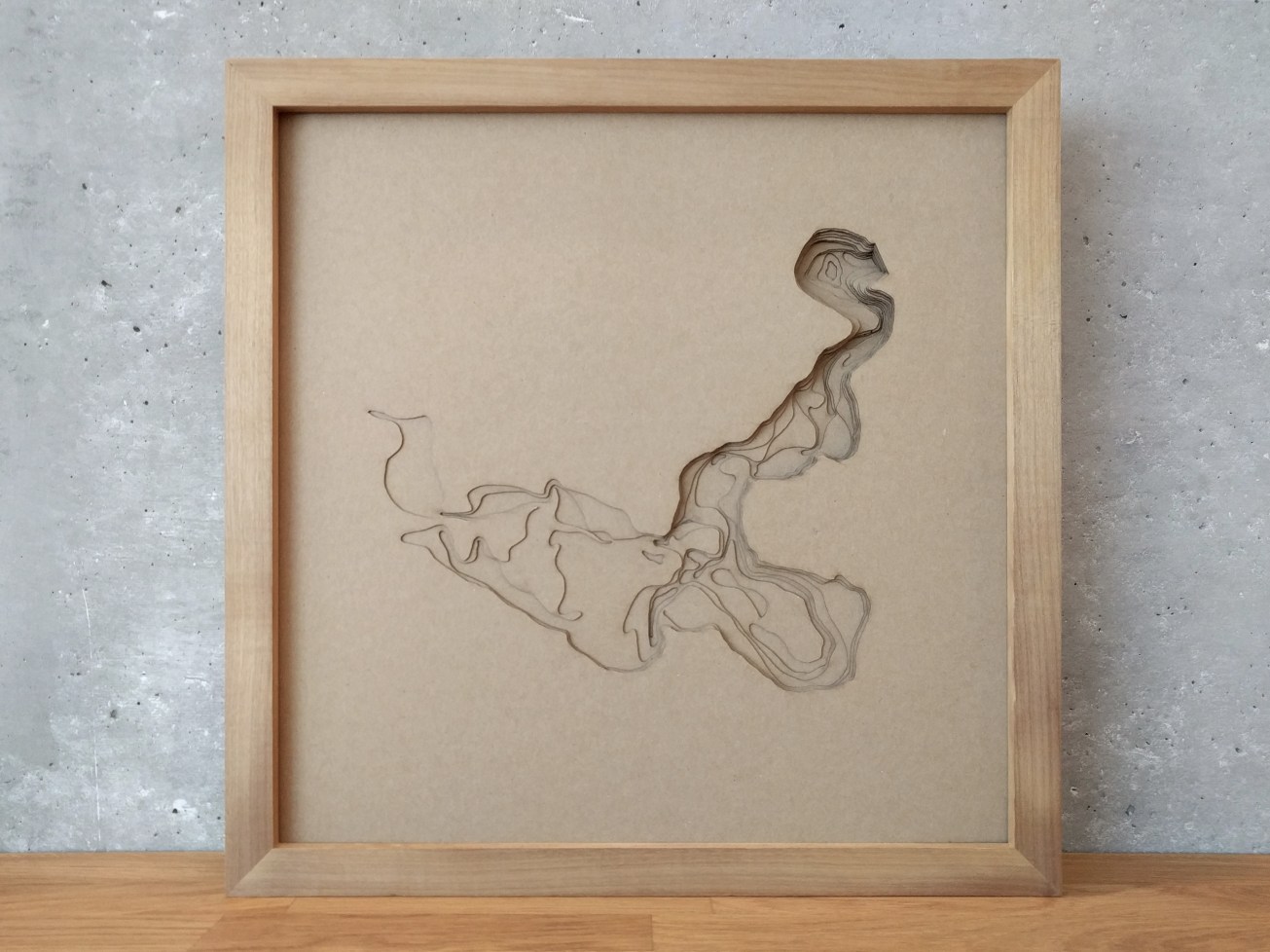

The resulting representational study, fabricated with laminated sheets of laser cut card stock, depicts the reservoir in all its enigmatic glory. It can be read with intense clarity within its depths, but without any contextual information from its surrounding surface, it floats in space as an autonomous object. To situate it, the viewer must interpret its depths and recognize the information inherent in its geometry. Luckily, this beautiful geometry tells a rich story. A story that meanders, veers off into long forgotten oxbows, and then back-flows from its imposing artificial barrier (the dam) upstream into a sprawled-out alluvial plain.